What Am I Making My Game With?

It’s been too long since my first post, but I’m still here working hard on my game about mycorrhizal fungi!

This post is about the tech journey my game has been on. From prototype to pre-production. It won’t be overly technical, so hopefully it will be informative to game developers in all departments, as well as juniors and students.

First Prototype

“Unity to be real must stand the severest strain without breaking.” Mahatma Gandhi

I started prototyping my game in the Unity Engine simply because it’s the engine I have the most experience with. I think that counts for a lot when prototyping, as speed is everything and you don’t want to spend your time learning new tools unless that’s one of the goals of the project.

So is Unity a good engine for prototyping? Well, it’s not bad if it is what you’re already used to. But really it depends on the nature of the game you’re prototyping.

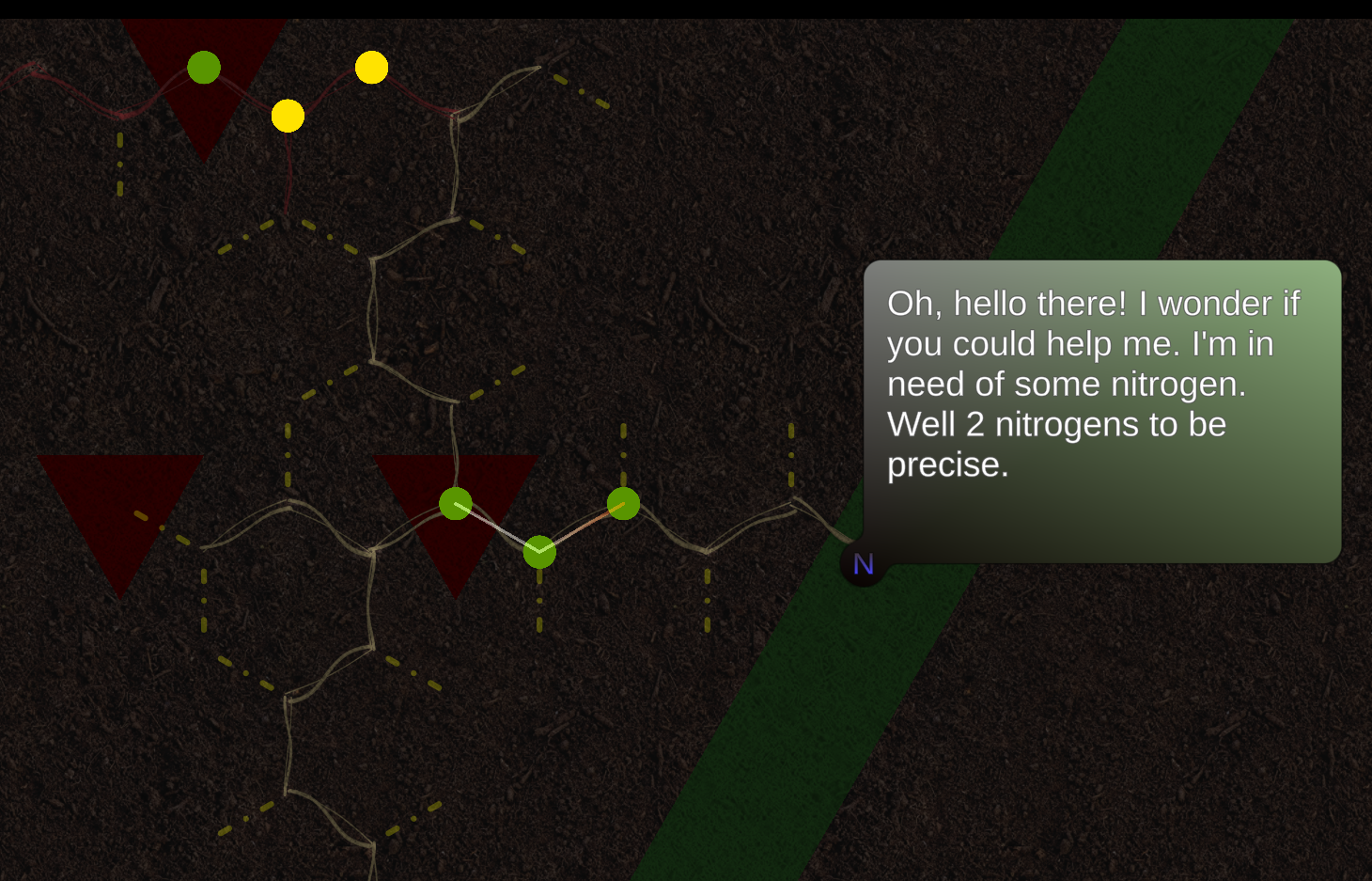

What my Unity prototype looked like in September 2023.

For 2D prototypes I actually think there are far better options than Unity. One that immediately comes to mind is Love2D.

I used Love2D for numerous prototypes way back before I discovered Unity, and I’ll argue that it’s a much faster way to prototype in 2D because you can literally draw a new shape onto the screen with a single line of code.

If you love it so much…

So why didn’t I use Love2D to prototype this project? Honestly, in hindsight I think I should have. Perhaps the only reason I didn’t is I expected to continue using Unity beyond the prototype phase, and therefore I thought it would be the least disruptive option in the long run.

I admit I had some flawed reasoning there because when you’re prototyping you can’t be sure that you will continue the project beyond the prototype phase, so you are best off choosing the tools that you can work fastest in regardless of what you imagine you would use in production.

Also if you’re consciously coding in a quick’n’dirty prototype manner, with no concern about the future stability of that code, then you’re uninhibited and probably much quicker at fulfilling the goals of your prototype.

And I didn’t end up using Unity in pre-production after all, so that imagined benefit of using it for the prototype didn’t materialise anyway.

Pre-Production

The prototype served its purpose. It taught me that a few of my mechanic ideas were rubbish, but I was then able to iterate on a few variations of those ideas until I had something that I was much happier to commit to. And ultimately I became convinced that there was enough of a worthwhile game in there to continue developing it long term.

But as I had been carrying this unchallenged assumption that I would continue developing in Unity throughout the entire project, I had spent a bit of time refactoring code to get things into a better state for long term development. To put that another way, I was no longer working in prototype mode, I had entered pre-production without really considering it much.

But then something unexpected happened that made me consider it very deeply.

Bye-bye Unity

In September of 2023 Unity shook the game dev industry with the bizarre announcement of their runtime fee pricing model. By that time I had been using Unity professionally (and for hobby projects too) for 14 years! (Plus 2 more years since then whilst I continued working at ustwo games).

Suddenly I was feeling far too invested in Unity for comfort. And in regards to this personal project of mine I asked myself;

What is Unity really providing to my project that I can’t get for free elsewhere, or develop myself within a reasonable time frame?

The short answer was; nothing at all.

But to be more elaborate, Unity was providing me with these 6 critical but not irreplaceable systems:

- A rendering pipeline, to draw things to the screen.

- C# programming language, one that I’m very productive with.

- An input API, so my code can respond to player input.

- An extensible editor, so I can make scenes, prefabs and custom tools for my game.

- Data serialisation, so I can save the things built in the editor.

- The ability to build for multiple platforms, including PCs, mobiles and consoles.

Time for something new

I had been searching for alternative game engines. I won’t list all the ones I looked at. I will just say that I came across no other engine that I was happy to switch to and commit to for the duration of my project.

So I started considering game frameworks. I discovered one called Monogame, a C# framework that is the spiritual successor of Microsoft’s old XNA framework.

It has been used to create many highly acclaimed indie games. The more I looked into it the more I liked what I saw. It would replace 4 of the 6 critical systems that Unity was providing me. It just wouldn’t provide me with any kind of editor or data serialisation.

The missing pieces

Well, data serialisation is certainly not a show stopper, since there are countless open source options available. I knew from work on previous games that there exists remarkably fast binary serialisation tools that produce tiny data files these days.

After a bit of research I decided to try using one called MemoryPack that I found on github, and so far it has worked really nicely.

So then the only thing missing was an editor. There are 3rd party options for level editing with Monogame, or any other game framework for that matter, particularly if your game uses a square grid.

But my game has very particular requirements since I bravely/foolishly opted for a triangular grid, rather than the common square or hexagonal grids.

Unity was sufficing before because its editor is extensible through scripting. But with Monogame it seemed I would be best off making my own editor from scratch.

Make your own

So I decided to do exactly that but with one key detail that I’ve become rather pleased about. I built my editor within the game itself, more on that shortly.

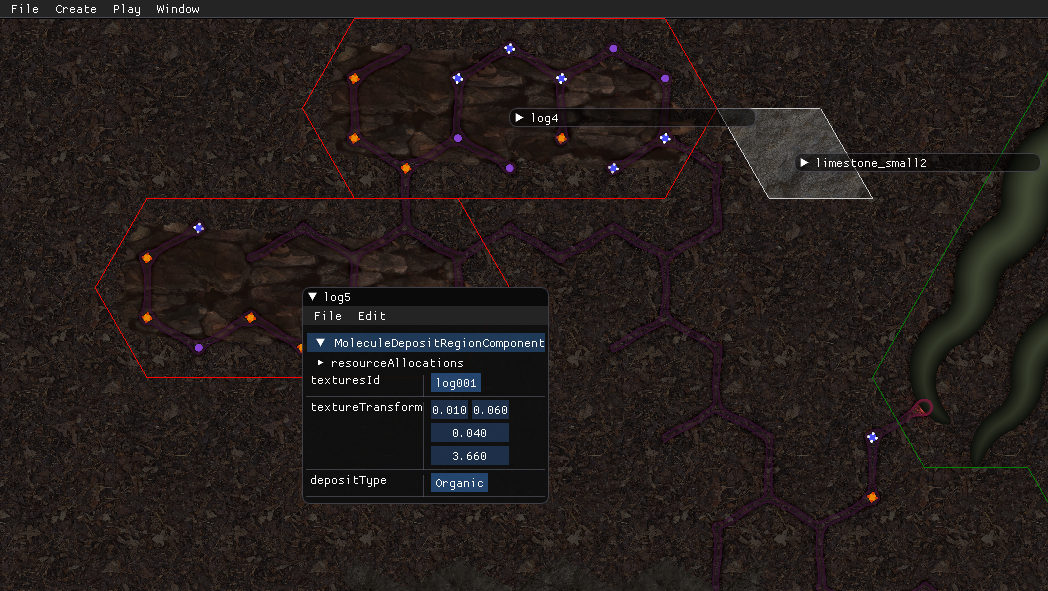

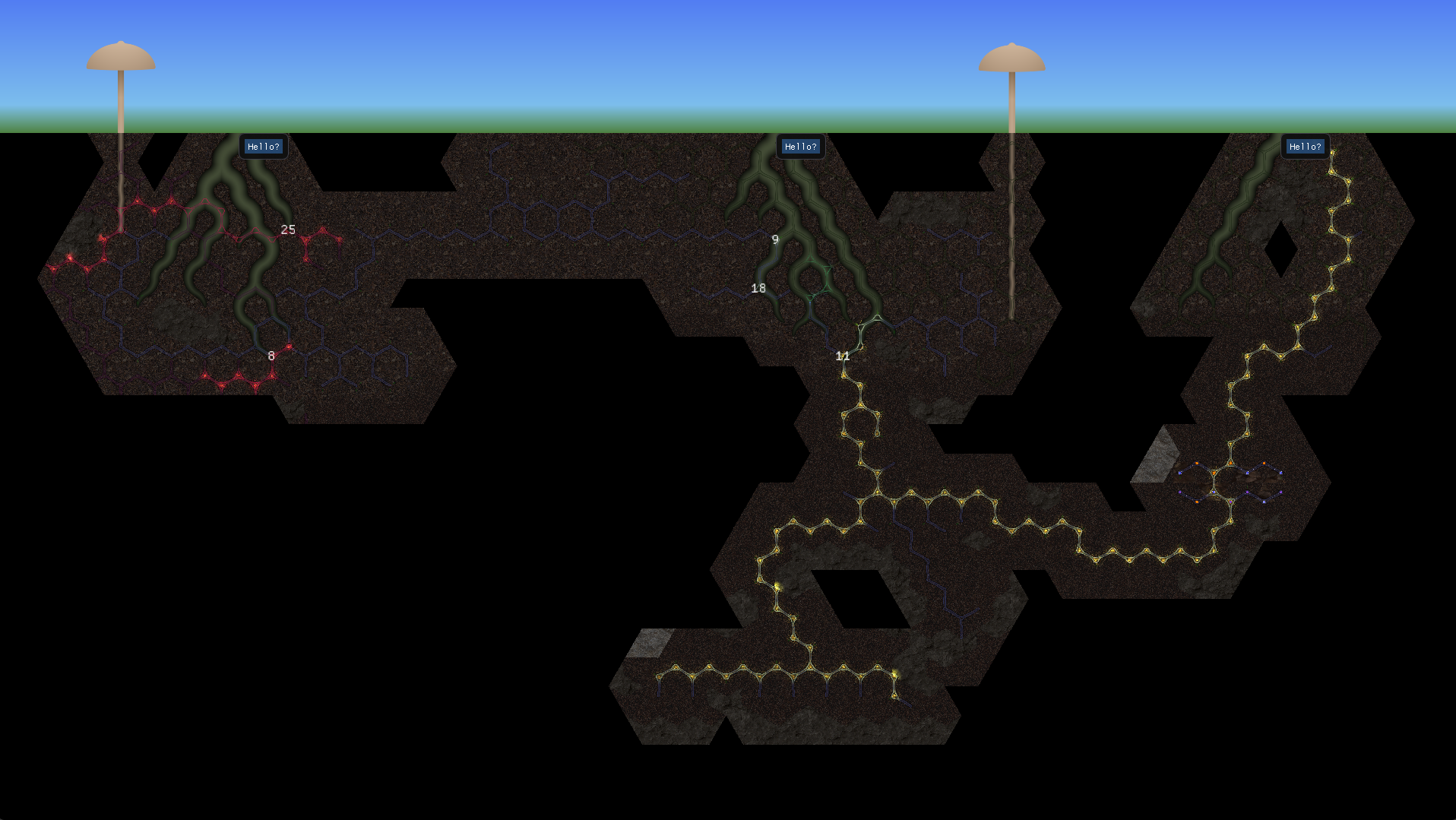

A screenshot of my editor in action.

The benefits

Building your own editor for your game, if you have sufficient reason to do so, is a really empowering thing. Making custom editor scripts in Unity is useful but ultimately you’re shoehorning functionality into a closed source application.

It can be cumbersome, restrictive and prone to the kind of bugs you can only guess at or work-around. You’ve got to learn the Unity way of doing things, rather than coming up with the way that suits your project best.

When making your own you are free to be inventive. Check out these skewed selection boxes I implemented which are helpful for level editing within a triangular grid for example.

Three different shapes of selection tools to aid with working in a triangular grid.

You end up with exactly the editor you need, no compromises, zero redundancy, and its super lightweight so loads in an instant. Also any bugs you find are solely within your own codebase so you can quickly debug and fix them without breaking a sweat.

The extra benefits

Making your editor run within your game build has some huge benefits that I didn’t even think of back when I made this decision.

The game and the editor can use the exact same systems. So any editor window that I write can easily be displayed during gameplay too for debugging purposes.

You might think; that’s no different to working in the Unity editor when entering play-mode. Sure, but then you’re likely also going to want developer tools within your builds. And there’s no way you can reuse your Unity editor scripts there. So you end up having to write tools for both the editor and the build, using two different UI systems.

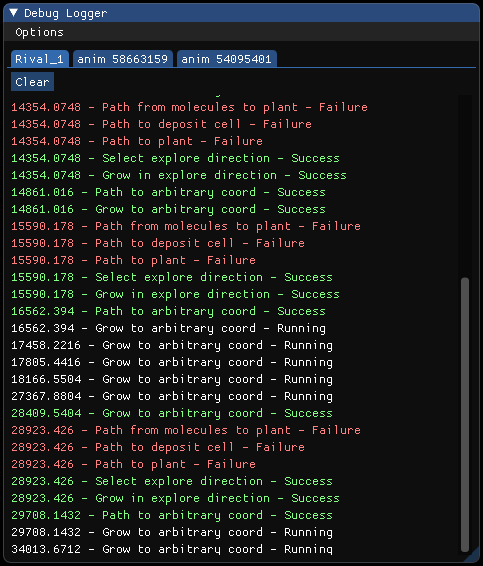

I picked one UI system for my editor, an open source project called Dear ImGui, and I use the exact same system for my in-game debug tools too. I’m even using it for prototype in-game UI elements until the time comes to pick something more aesthetic for the final product.

My debug logger UI window made with Dear ImGUI. Complete with tabs so logs from different systems stay organised.

The same is true of the serialisation tool I integrated, MemoryPack. I use it in edit-mode for saving scenes, prefabs, components and their data.

And I also use it for saving the current state of the game in play-mode.

In fact all of those things are completely interoperable. I can take a player’s game save, load it up in edit mode, change whatever I want then save it as a scene, or part of it as a prefab.

I also use the same system for turn-by-turn game snapshots, so I can step backwards some moves after witnessing a bug and make it happen again, this time with the debugger armed. I can then also save that just-prior-to-bug game state as a test scene so that I can come back to fixing it later, and use it as a regression test after it has been fixed.

Final Thoughts

If you’re a veteran game programmer perhaps you’re thinking “yeah, of course, this is how we use to do things”. But this all seems like a dream to someone like me, who learned most of what I know inside the confines of a 3rd party engine.

I’m certainly not going to argue that every game would be better off having its editor built into the game. Beyond a certain level of complexity you’re really not going to want that. If you’re having to author large 3D environments with many different meshes, textures, LODs, lighting, and need to bake various kinds of texture maps, and so on… then of course that would be a nightmare to use anything other than standalone software.

But I’m making a game that is technically quite simple. And indie developers will continue to make technically simple games for decades to come because we’re far from out of ideas, and players are far from bored of our ideas. So I think this approach is completely relevant today and well worth sharing.

Runtime fee legacy

You might be aware that Unity eventually scrapped their “runtime fee” plans. So I could’ve just continued developing in Unity, and it wouldn’t have been a big deal.

But I’m glad that it put me on this other route. It immediately made the project so much more fun to work on. And now that I’m up to speed with my own custom editor and slick workflow, I feel much more in control of my own destiny, to the extent that one ever can feel.

Your reward

Here’s your reward for reading all the way to the end…

A bonus screenshot of the game in its current state.